By Manny Soriano

[For this month’s Lasang Pinoy, I am glad to once again host an entry contributed by a Filipino-Canadian food and music enthusiast. He was born and educated in the Philippines and migrated to Canada in 1971. His mother was an excellent and practical pastry and savoury cook who operated a hotel with his father who was a coffee and cigar connoisseur. Manny started baking in highschool and worked as an accountant till 1999. He took baking courses since 1990 and opened a Filipino pastry shop in the west end of Toronto in 2000. – Karen]

If the movable feast aspect of our streets spoiled you, swelled your head and made you think streetfood is uniquely ours, think again. Walk along the cobbled streets of Salvador de Bahia and you will find rows of immaculately dressed ladies selling shrimp flavoured red fritters that once tasted transports you back a world away to Aleng Asyang’s okoy from just around the bend. Don’t even get me started with Mexico. In fact you can find streetfood just about anywhere the rational, sanitizing, regulatory mindset has not yet imposed its will upon people’s native sensibilities. In neighbouring countries justly celebrated for their streetfood, totalitarian obsession for civic tidyness has now began to rear its head, this time to compel hawkers to toe the line and gather under the watched-over roof of food courts. A really foolish if not impoverished trade-off for the freedom, surprise and serendipity of traditional streetfood scenes, if you ask me. Besides, the allure of streetfood is discovering it right there and consuming it right then, with as little delay as possible and certainly without having to detour first to an officially designated concentration centre. You see, we are all impulsive four-year-olds when it comes to food. We want it when we want it. Satisfying this urgent need is streetfood’s primal appeal.

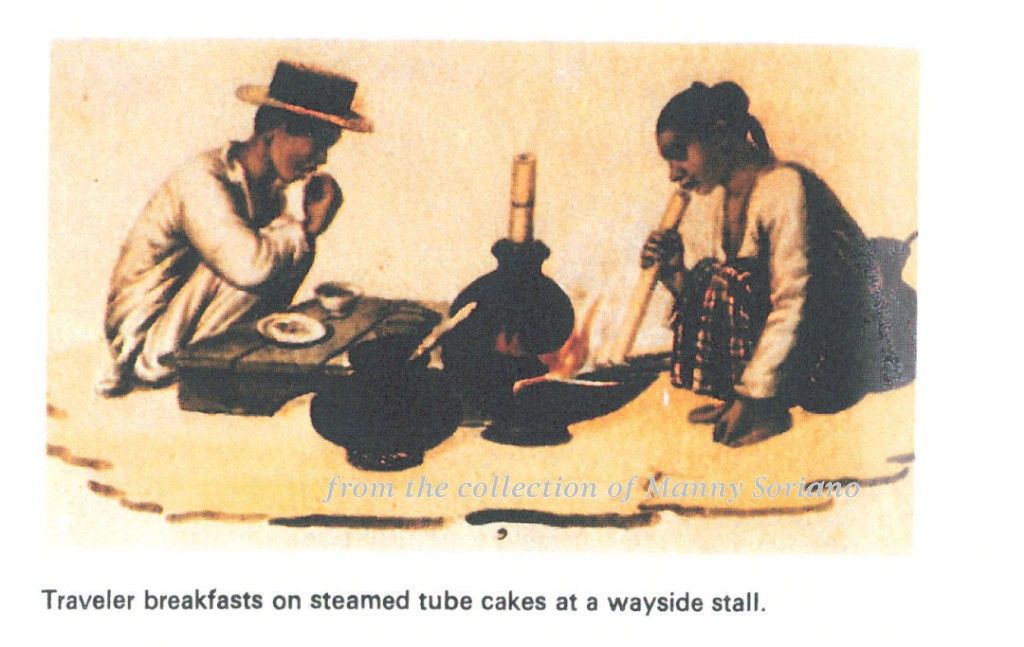

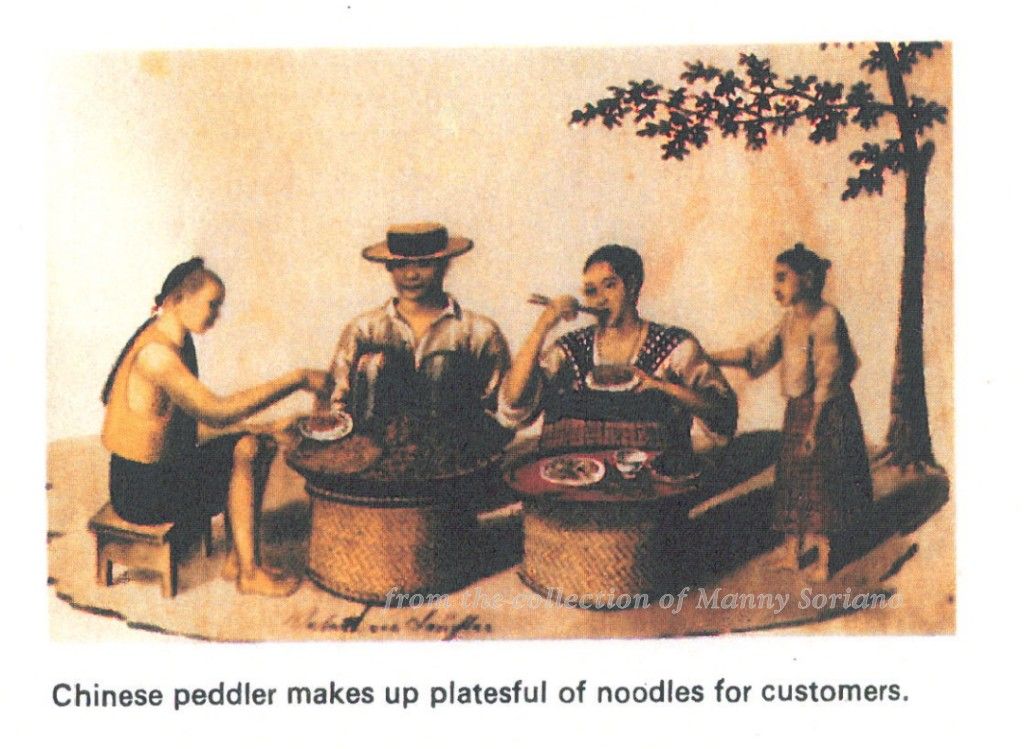

People ask what’s with this obsession about food in developing countries such as the Philippines. Are we just overcompensating for the constant fear of hunger? No, not really. A growing number of us suffer sporadic deprivation to be sure but there has never been any large-scale food scarcity here that it would loom large in our consciousness. Neither history can cite nor memory can recall even one. I do not think either that we are orally fixated as a nation more than any other. Why then do our cities and towns present us with such bewildering array of streetfood? Could it be that there is so much under-utilized manpower available that we can afford to lavish it on the preparation of all this labour-intensive recipes? Or perhaps their production demands a patient dedication that only individual or single family enterprises can sustain. Hence, the anarchic profusion. It strikes me too that it has always been so, entrenched, traditional, eternal, partly attributable only to our common Chinese heritage. In that case then, a lot of our food must have began life as streetfood, exactly as a couple of them depicted in a German traveller’s drawings from the 1850s.

Back to my little town in Bataan, just a few miles away from the lights and madding crowd across the bay, daily life could not have been more rural or different from that in the1850s. Life had reserved the ceaseless cycle of the seasons of growing rice or tide’s recurring rise and ebb dictating the moments for setting out to sea to fish. Food specialties followed blood-lines as surely as peculiar traits or reputed possession of occult powers. It was easy enough to grasp that a recipe whether to nourish or to hex is best handed down from parents to children. We knew from whom to avert our eyes and who of each generation made the best puto and buboto, okoy, bibingka and suman, espasol and tikoy*, lechon and salsa, bagoong and buro, tuyo, daing and tinapa. For special occasions we ordered ahead, but for the all too often spur-of-the-moment cravings, all we had to do was seek them out at their home early, intercept them on the street or just catch them later at their stalls in the market. Theirs were the recipes that it never occurred to anyone to take the trouble to write down and learn simply because they have always been there, accessible, satisfying, permanent. Not quite. Certain items drop out and disappear from lack of interest but more often neglected due to scarcity of critical ingredients (such as precious time) and are waylaid, forgotten, endangered. From time to time though a rare delicacy that everyone assumed everybody had forgotten makes an appearance and with just that one quick tiny bite summon back all the vivid images of those kind souls who made them, the enterprising young women who balanced them on their heads to market, your mother and sisters who brought them back for the family and the uncles and friends you enjoyed them with afterwards. Each and everyone, now passed on and gone forever.

*Tikoy made the rounds in my town at two in the afternoon. They called them out with puto-bungbong which, following the aleatory nature of Filipino food naming, were actually cylinder-shaped espasol. They can be flavoured with either pandan or anise. Either one turns out great with tea the whole year round. Keeps forever in the fridge or freezer too.

Easy Tikoy

1-1/2 cup glutenous rice flour (Mochico)

3 cups water

1 cup granulated sugar (or to taste)

3 blades of pandan

pinch of salt (or a dash of anise seeds)

Boil blades of pandan until water turns pale green and scented. Discard pandan, pour water into a mixing bowl and allow to cool down. Stir in rice flour, sugar and salt until blended. Let stand for an hour. Stir again before pouring to a depth of 1/3” in a 9” x 9” square pan lined with foil. Steam vigorously until firm and translucent. Beat remaining mixture again before pouring the next batch to steam. Set aside uncovered for the surface to dry before wraping in greased foil to store in the fridge for at least a full day before slicing each large square into 16 small squares. Fry until golden brown and the edges are crunchy.

Update: Kai’s round-up for LP3 is now online.

Leave a comment