When talking to our town’s renowned cooks, I ask about how long they have been cooking and who taught them to perform magic in the kitchen. Some took cooking seriously very early, some as young adults but to a person, each one had kitchen duties as children. Everyone remembers receiving methodical instructions from their mothers, fathers, grandparents or relatives who were also accomplished cooks. It seems as if they spent years of apprenticeship in the informal setting of home kitchens.

Iska’s theme for Lasang Pinoy 8: Kusinang Bulilit, Lutong Paslit! has made me realise that I would love to explore the topic of informal apprenticeships in the future. For the meantime, I’ll have to remember how I started cooking as a child since the only juvenile I have around is a gigantic kitten who perches on the kitchen bench as soon as I start with prep work.

Pampanga has a long tradition of trade, arts and crafts long before the arrival of the Spaniards. Pre-colonial society had a system of apprenticeships where the youth got to learn their craft from the masters. To a certain extent, I still feel vestiges of this practice when I see and remember how children are sent off to “help out” relatives during fiestas and other special occasions. In many traditional families, it does not matter if one is poor or with a house attended by servants. Each child, whether male or female, is expected to help out with household chores.

It was this philosophy that ruled me from my early years. When I asked my mother how come we had to learn the small details of let’s say polishing brass or scrubbing the floor when we could ask a helper to do it, with patience she replied that we cannot command anyone effectively if we do not know how to do the task ourself. How can you instruct someone to do what you want when you can’t do it yourself? That silenced the smart alecky brat that I was.

In the kitchen, my grandmother – Lola Felisa, was my mentor. She was patient enough to start me with the simplest of tasks but would raise hell with repeated mistakes. I don’t remember her holding my hand in any of my assignments. Instead, I felt that she was confident that I would accomplish whatever she set me out to do. Hmmm… good mentor indeed! I suppose that’s the only way to go. No spoon-feeding, no coddling.

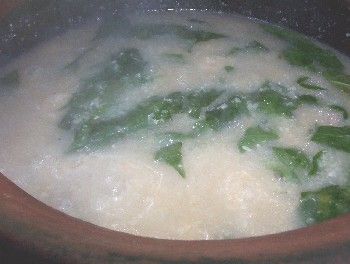

In my opinion, the best way to start a child cooking is to let him or her watch and then graduate into simple tasks. One of the dishes I remember “graduating” into is suam mais, a thick creamy soup made from white glutinous maize (corn). I was trying to find the etymology of suam but and I’m not close to finding it. In Filipino cooking, it refers to several clear but chunky soups, e.g. suam ema (crabs), suam ebun (eggs), etc. In Bahasa, the word ’suam’ is temperature related, approximating tepid or lukewarm. I am not sure if this is at all related to how it evolved in the Philippines or if it is another one of a myriad names for ’soup’.

The first task I did to help cook suam mais was to grate the maize on my grandmother’s old-fashioned grater. The maize has to be the white, sticky variety, not “yellow sweet corn” which will not yield a creamy consistency.

As I grew up, I was allowed to handle more of the tasks until finally, needed no supervision. Each step didn’t require much from me since they were taught gradually. When I think of teaching children how to cook, I don’t think of specific methods or beginner’s recipes. If and when I do have children, I’ll probably do as I was taught. Approach cooking as an everyday function, like eating, brushing the teeth and taking a bath. Pretty soon, it will be second nature to the child, just like the best cooks in town.

Suam Mais

10-12 cobs of white, sticky maize

1/2 kg. chicken, shredded or cut into small chunks

2 heads garlic

1 cup chilli leaves

1 tsp. cooking oil

salt and pepper

4 cups water, approx.

Unhusk and clean the maize. Make sure all kernels are full and fresh. Grate gently so as not to include the cob which is very tough.

After grating, soak the cobs in tepid water for at least five minutes. With a knife, scrape each ear, letting the germ fall into the water. Set this aside. In the meantime, sauté the garlic then the shredded chicken. Season with salt.

When the chicken is lightly brown, pour approximately 1/3 of the water with the scraped maize and simmer for around 10 minutes. Add the grated corn and simmer again, stirring constantly to prevent it from burning (don’t forget, starch scorches easily). Pour in the remainder of the water and let it boil for around five minutes. Every now and then, pour approximately half a cup of water, simmer then stir. It is done when the maize is almost transparent. Add the chilli leaves then turn off fire. Cover and let stand for around 5 minutes.

A nice bowl of suam mais is a meal in itself but Filipinos eat it with rice, naturally. 🙂

Leave a comment