This was supposed to be posted on the eve of New Year’s Day but I was still out of sorts after the Indian Ocean calamity, not knowing how things were out there, praying and feeling helpless. I had to spend more time with my own thoughts, trying to make sense of the situation. While efforts are being done to help the victims of the earthquake and tsunami, perhaps it is best to use this web space to remind us, myself most especially, that such destruction shall also pass.

I can say this confidently because 13 years ago, we were in the midst of a catastrophe, of a lesser magnitude no doubt, but we also felt helpless and hopeless. Today, we have not yet fully recovered from the devastation of Mt. Pinatubo yet a lot has already improved. Most people have gone on with their lives, some farms are already rehabilitated that we have to think of ways to maximise the harvests that would just go to waste. Life has become quite normal, in fact that for three years now our town has been celebrating the Duman Festival, partly to revive a vanishing tradition and partly to celebrate life after devastation. What better way to be grateful of how we overcame destruction than through a rice festival, the symbol of prosperity in many Asian societies?

Three years ago, some brilliant townmates came up with the idea of reviving a tradition which almost vanished in the wake of Mt. Pinatubo’s eruption. Most of the rice fields having become productive once again, all was set.

Duman is a rare rice cereal which originated in Santa Rita. I suggest you read the excellent article written by Tonette Orejas after the first festival; nevertheless I’m still going to quote heavily from it:

“Duman-making, as a clan-based culinary art, spread to the nearby towns of Bacolor, Guagua, Lubao, Porac and Floridablanca. By the turn of the 20th century, it became a favorite in the popular local trade of Kapampangan delicacies.

“Still, the duman from Sta. Rita reigned, Cuenco said. Duman-making, he said, was also why the rice variety lakatan malutu (malagkit to Tagalogs) has survived pestilence, earthquakes, floods, wars, volcanic eruptions and other disasters.

“The rice variety is planted beginning June, Cuenco said. Fertilizers and pesticides are never used. Its source is unknown but sometimes traced to Chinese traders in the town of Guagua (Wawa) in the early 1800s, he said.

“A good part of the harvest is stored to protect and sustain the vanishing variety found only in Sta. Rita, Cuenco said. “No other grain would do. It’s not the duman unless the same variety is used,” he said.”

Now that I come to think of it, I wonder if anyone thought of entering this in the Slow Food awards. I should look that up!

Anyway, duman is quite an expensive treat, as I remember how my grandmother would tell us to not waste a single grain. This year I found out that a pati (2.5 kilograms) costs around PhP2,000.00 (approximately US$ 36). How did it become that expensive? The rice variety that is used can only be harvested once a year compared to the three harvests of the more common varieties. Moreover, with the lacatan malutu (literally red glutinous rice), each hectare has a yield of only 30 cavans (cavan = sack) while commercial varieties yield 300 cavans.

For this entry, I planned on taking pictures and writing about the whole process of getting the duman from the field to the table but it was not meant to be. To remedy the damage, I borrowed pictures from the organisers of the festival, the Artistang Sta.Rita Foundation or ArtiSta.Rita for short (in the next few weeks I will write about this exceptional group, which brought about the renaissance of the arts in our town). They obliged and lent me a whole CD of pictures like the one above, and some with captions (from Claude Tayag, if I’m not mistaken), which you see below:

After harvesting the rice, the grains are separated from the stalks. Traditionally, this was done by forcefully striking a hard surface with the rice stalks till the grains fall then gathered in igu or bilao/bamboo trays, tossed in the air to sift out the debris (tatap). The grains are then gathered and moistened.

Note: the wide-mouthed basket above is a salicap – the picture of an igu/bilao is at the bottom of the entry for bico.

The rice, still with the hull, is then toasted or sangle in an oven-like clay pot. The process is long and arduous, and usually carried out by the menfolk.

After around 2 hours, the single or toasted grains are left to cool in the open. This is when the action of the bayú (pounding) is about to begin.

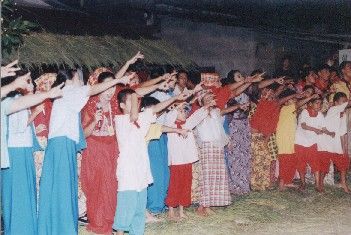

Upon cooling, some of the grains are then transferred in large wooden asung (mortar), with three men rhythmically taking turns pounding with the alu (pestle). At this point, the merrymaking would have started with everyone singing traditional folk songs, both playful and lyrical. I was in awe at how the motion seemed to have been fully choreographed, the pounding unconsciously following the beat of the music. This is probably the most labour-intensive step as it takes five rounds of pounding, each round for a specific purpose, such as to break the husk, to flatten the grain, and so on. After each round, the rice is transferred in the igu for another round of tatap.

Hmmm… aside from the Slow Food events, I wonder if duman-making can be considered an Olympic sport, since the pounding is non-stop for hours (endurance) and has to be perfectly synchronised (coordination) otherwise a lot of injuries would arise out of it.

The result of a whole day of this extremely physical undertaking – from harvesting, winnowing to pounding – is a flattened light golden green rice cereal. If harvested extremely young, it has a melt-in-your-mouth consistency and a milky taste. A more mature harvest renders a grain which is best toasted till puffy, or what is known by Tagalogs as pinipig, except that what is now sold commercially is just ordinary rice, not duman.

In many Pampanga markets, one can also see fake deep green duman sold by the glass, and green calame (kalamay or rice cake) which is supposedly duman and a 2-inch square sold for ten pesos. Ha! Real calame duman of the same size will be at least worth a hundred pesos!

In the future, I hope to implement my plans and also interview the families who still plant lacatan malutu for duman. Since my field is in environmental management, I wish to know how they were able to save the rice variety when a good part of our town was evacuated during the Pinatubo eruption and for years afterwards. It would be good to find out, who knows if we might learn some lessons in indigenous conservation strategies!

In this season of catastrophes, it is good to be reminded that life will find a way to be.

Leave a comment