In an attempt to efficiently enforce taxation, on 21 November 1849, the Spanish Governor General Narciso Clavería ordered a systematic distribution of surnames for the native population. Names from the Catalogo Alfabetico de Apellidos were assigned to families in all towns. The distribution was in alphabetical order and caused some small towns with only a few families to end up with all names starting with the same letter.

To the outside world, Filipinos may seem to be almost Hispanic, with surnames, food and other legacies of the 333 years of Spanish rule. But there is more than meets the eye, something more complex. A cursory glance at something as plebeian as our streetfood is already an indication. Take for example our tamales. It has a deceptively Mexican name but its essence can only be Filipino.

In the country, especially for Capampangan s, it is always in the plural – tamales – even when singular. There are different recipes but the best tamales in Pampanga were said to be those from Cabalantian in the town of Baculud (Bacolor). Fiestas and special occasions would not be complete without several dozen made-to-order tamales. These would be exceptionally flavourful and packed with meat that one parcel could be considered a meal. On ordinary days, ambulant vendors would and still do ply the streets selling capangan (kakanin in Tagalog, loosely translated to snacks, usually rice or rootcrop-based) which include tamales. Everyday tamales, however, are less rich and slivers of meat more sparingly arranged. This is actually more akin to the native bobotu, the pre-Hispanic rice-based snack cooked with coconut milk and wrapped and steamed in banana leaves. The Mexican tamal meets the native bobotu, takes on the Mexican name yet retains its pre-Hispanic character.

This meeting of the East and West and the indigenisation of imported or ‘migrant’ food items is also apparent in the quiltian mais or binatog. Maize or corn (Zea mays) was also introduced through Mexico in an attempt to replace rice as a staple (hmmm…?!?!?!). It did not gain wide acceptance but was turned into snacks, soups and sweets. Camote or sweet potato (Ipomea batatas) was brought to the Philippines from Mexico and is boiled, roasted, fried and skewered and called camoteque (camotecue/camote-q).

Peanuts (Arachis hypogaea) are an ubiquitous streetfood item. Known locally by its Caribbean name mani, they are boiled, roasted, made into candies or fried with or without garlic, chillies. Fried garlic peanuts are referred to in the Tagalog region as adobong mani, with reference to the manner of cooking with garlic and spices. The different methods of cooking peanuts are also used for other nuts such as balubad/casoy (cashew, Anacardium occidentale L. – native to Brazil, brought to India by the Portuguese – to the Philippines by what route, I’m still sleuthing) and the indigenous pili (Canarium ovatum).

On a more Oriental note we start with what Doreen Fernandez calls the “direct heirs of the Chinese vendors who carried paired baskets balanced on shoulder poles”. One of these is the vendor of taho (soft soybean milk cake and syrup) who takes his day’s supply from a factory and peddles it on his regular route. For my purpose, I interviewed the taho vendor and found out it is made in San Fernando and brought to Sta. Rita very early in the morning. The factory used to be owned by an ethnic Chinese but has been bought by a Filipino-Capampangan. Hmmm…

Buchi/bochi is a snack with counterparts in many Asian countries. It is usually sold in igu/bilao or bamboo trays lined with banana leaves by itinerant vendors walking their route around town or in marketplaces. Buchi are made from ground glutinous rice filled with sweetened mung bean paste then fried to the the point it forms a crusty shell but remains soft inside.

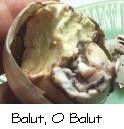

Another food item we share with other Southeast Asians is balut (called hot vin lon by the Vietnamese and bong dia gon by Cambodians), a boiled fertilised duck egg. Believed by many to have rejuvenating properties it is a favourite pulutan or drinking food also given to convalescents. Balut is also said to be an aphrodisiac and is sold everywhere – “on the streets, at stalls, outside movie houses, outside nightclubs and discos, in markets; by vendors walking, sitting, or squatting; at midnight and early dawn, at breakfast, lunch, merienda and dinner time” (Fernandez, 1994). Not all Filipinos eat balut but it is culturally well-regarded that it has even inspired a song –

Balut, penoy, balut

Bili na kayo ng itlog na balut

Sapagkat ang balut ay mainam na gamot

Sa mga taong laging nanlalambotBalut, penoy, balut

Bili na kayo ng itlog na balut

Sapagkat itong balut ay mainam na gamot

Subukan nyo, pampalakas ng tuhod.

One facet of streetfood worth mentioning is the sense of community that it fosters. In fishball and barbeque stalls, patrons stand side-by-side waiting for their orders to be done then dip them in a common jar of sauce. The fact that food is sold, bought and eaten in public where community-members mingle, unwind and learn from each other is part of the whole experience. How many times have the customers waiting for their orders or eating found themselves chatting despite being strangers attests to streetfood’s very social nature.

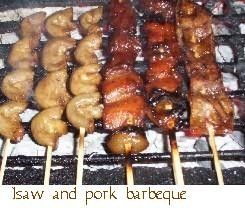

For this month’s Lasang Pinoy, I tried to break out of my comfort zone and partake of streetfood I never had before. Off I went to where Sta. Rita’s barbeque stalls line the street to buy and interview the sellers.

What at first seemed like skewered wafers akin to uncooked prawn crackers are actually squares of pork skin with the fat trimmed off, cooked adobo-style then grilled. What results is a tender yet chewy morsel of meat which hints at chicharon except that it’s not puffed. This is said to be a relatively new addition to the line of barbeques. The current price is PhP 5.00 per stick.

The highlight of my interview was finding out that there were actually two kinds of iso/isaw – pork (pictured on far left) and chicken which is called IUD. Iso/isaw is the small intestine of an animal and according to the sellers, they prefer this because it is cleaner than the large intestine used for chicharon bulaklak (puffed large intestine cut into bite-sized pieces). The preparation of this part is also given careful attention as it is cleaned well, boiled with a bit of vinegar, scraped then pre-cooked (adobo) before finally being skewered for grilling. At PhP 5.00 per stick, I thought the price is not commensurate to the work. The smell wafting from the grill was also far more pleasant, “cleaner” and more flavourful than the barbeque stalls I often encounter in Metro Manila. But then again, I forget that I was in the province that could probably be the culinary kaartehan (fastidiousness) capital of the Philippines and shortcuts are frowned upon especially in a small town where everyone knows everyone else.

Although litson/lechon manok (roasted chicken) is in the higher end among streetfood and may not be as affordable as its other grilled counterparts, I consider it as what embodies the Filipino spirit. Its emergence is rooted in adversity, according to my late uncle who knew the family that originated the chain of stalls in the 1980s. It appears that they were a supplier of poultry for a large outfit and for some reason the chickens could no longer be taken. Instead of letting a disastrous situation befall them, they were able to strategise well, put up a few stalls that would soon start a litson manok craze and two decades later, the concept was copied by almost every town and city in the archipelago and it seems like lechon manok is here to stay.

Food, they say because it is visceral, is so basic to the understanding of a culture. I go back to the tamales. As new foods and new methods of cooking are introduced into a culture, an adjustment takes place, not only of the receiving culture by accomodating the new concepts but also by the ‘new’ foodstuff. Native to us is the bobotu, a savoury ground rice, banana-leaf wrapped food parcel. For this reason, the imported Mexican tamal did not seem that much of a stranger. In the process of co-existing, the former was thus influenced into adding colour (achuete/achiote/annatto), ground peanuts and strips of meat into the mixture. The latter, on the other hand, adapted to the local setting by using ground rice instead of cornmeal and was cooked in coconut milk. The tamales was then wrapped in banana leaves instead of cornhusks and as it exists in the country, has become very different from what it originally was.

From tamales to balut to litsong manok – these are the food items we see on the street. They may have come to us from different sources and circumstances but as soon as they’re here to stay, they become irrevocably Filipino.

My gratitude to Kai, for hosting this month’s event. If it was not for this theme, I wouldn’t have discovered what I’ve written above, and many more.

Update: Kai’s round-up for LP3 is now online.

Leave a reply to A curious culinary journey: discovering local street food – The Pilgrim's Pots and Pans Cancel reply